Developing allotments

8th September 2014

Background

The term allotment usually refers to land held by a local authority under the Allotment Acts 1908 – 1950 however it is also possible for allotments to be privately owned. Privately owned allotments are however still governed by the statutory provisions relating to the determination of tenancies and payment of compensation and therefore disposal of land which is the subject of such tenancies can be complicated by the need to follow those statutory provisions in order to regain possession of the land in question.

Type of tenancy

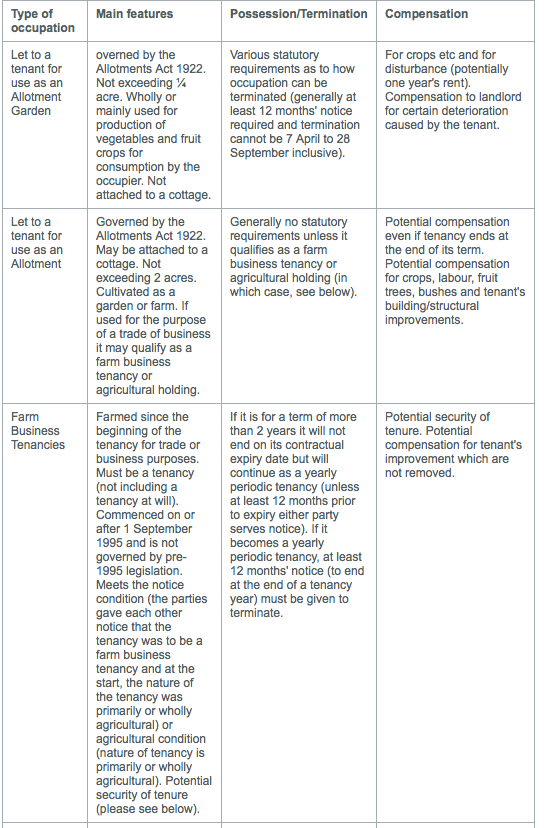

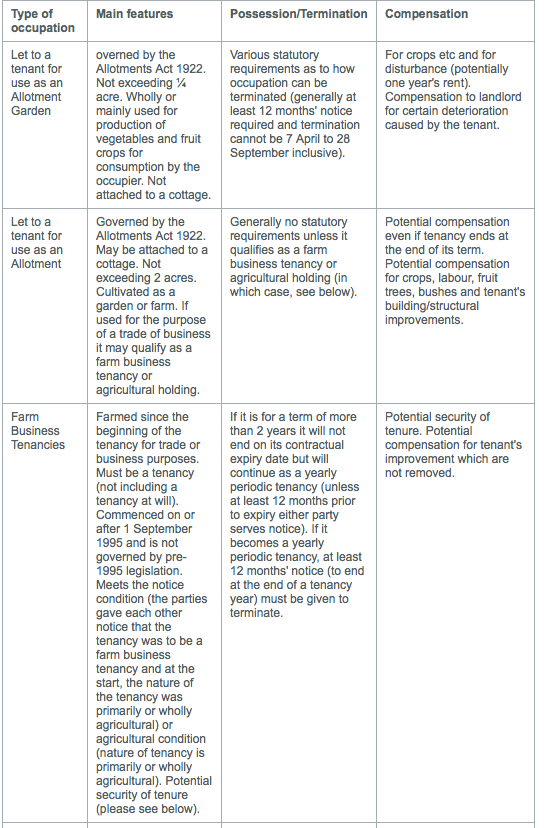

The first step in compiling a strategy for disposing of land which is the subject of allotment tenancies is ascertain how the tenancy can be determined but in order to do this it is necessary to assess what type of tenancies are actually in place. Unfortunately, in many cases this is easier said than done as it may often be difficult to assess which type of occupation a particular allotment tenancy falls within. Whilst the tenancy documents may contain contractual termination provisions, it should be noted that regardless of the termination or compensation provisions in the relevant tenancy document, these may be overridden by the statutory provisions. The table below sets out a brief overview of the main types of allotment tenancies (which are further considered later in this note):

Agricultural Acts

There are various Allotments Acts which contain statutory provisions covering termination of allotment tenancies and payment of compensation. As can be seen from the table above, the Allotments Acts distinguish between ‘allotment gardens’ and ‘allotments’. ‘Allotments’ may qualify as ‘agricultural holdings’ or as ‘farm business tenancies’ under statute if used for the purposes of a trade or business.

Allotment Gardens

If an allotment is let on a tenancy for use as an allotment garden, regardless of the provisions of the tenancy document, the tenancy cannot be terminated other than:

- by giving at least 12 months’ (which cannot expire after 6 April or before 29 September in any year)

- by three months’ notice if the land is required for building, mining or other industrial purposes or for roads or sewers necessary in connection with these purposes

- in certain other scenarios, including for corporate landowners as owners of a railway, dock, canal, water or other public undertaking, breach by the tenant of the tenancy or tenant insolvency or

- re-entry for non-payment of rent, breach of the terms of the agreement or bankruptcy of the tenant.

Compensation is potentially payable on termination of the tenancy and this is regardless of whether compensation is excluded in the tenancy agreement. Furthermore, the landlord may also be entitled to compensation for deterioration of land.

Tenants of allotment gardens and allotments have certain rights to remove fruit trees and bushes and fencing/improvements etc carried out by them subject to an obligation to make good damage. Further, in certain circumstances the tenant may have rights following termination, such as to remove crops.

Allotments

There are limited statutory provisions regarding termination of allotments but if the land has been used for the purpose of a trade or business, it is possible that such allotments can be classified as farm business tenancies or agricultural holding meaning that the statutory provisions relating to these types of agreements would then apply. Provisions for compensation differ to allotment gardens and can be payable for crops, labour, fruit trees, bushes and improvements made by the tenant to buildings and structures. Such compensation can even be payable if the tenancy expires naturally by effluxion of time.

Farm Business Tenancies/Agricultural Holdings

An allotment tenancy agreement granted after 1 September 1995 will be subject to the provisions of the Agricultural Tenancies Act 1995 if the relevant qualifying conditions (set out in Schedules 1 and 3 of that act and which amend the Allotments Act 1922) are met. If the land is for the purpose of a trade or business and meets either the notice condition or agricultural condition it will be a farm business tenancy. If occupation is under a farm business tenancy for more than two years, rather than occupation terminating at the end of the term, it continues on a yearly tenancy and at least 12 months’ notice to terminate (to expire at the end of a tenancy year) is required to bring the tenancy to an end. Furthermore compensation for tenant improvements may be payable. If occupation is by certain types of agricultural holdings, there are more onerous termination provisions and tenants can resist notices to end the tenancy.

Security of Tenure

Security of tenure under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 may if the occupation does not fall within the agricultural statutory regime or is a farm business tenancy. Some tenants may therefore acquire rights to remain in occupation of a leased property at the end of the contractual term and the tenant may require the landlord to grant a new lease.

Security of tenure requires occupation for the purposes of a business. In terms of occupation, this is likely to be satisfied by the users of allotments. ‘Business’ has a wide definition and includes trade, profession or employment and there are various principles as to what constitutes a business. This will be fact dependent.

If a lease has security of tenure, the landlord must serve notice if it wishes to terminate the lease at the end of the term. To validly serve such a notice, the landlord must satisfy one of the grounds of opposition. These grounds include certain tenant faults (such as disrepair of the property or arrears of rent) or the ‘no fault’ grounds, such as the landlord having a genuine desire to occupy the property itself (which requires the landlord to have owned the property for at least five years) or plans to redevelop the property which is prevented by the tenant’s occupation. If a new lease is successfully opposed on a ‘no fault’ ground, the tenant is entitled to statutory compensation.

Strategies for the transfer of allotments

If the tenancies in question cannot be terminated in order that a sale of the land with vacant possession can be achieved, the sale will need to be made subject to the residents’ interests in them.

Where multiple allotments are owned it is likely to be impractical to sell off the allotments as individual plots to the relevant allotment occupier. Each purchaser may well require different terms for the transfers, and it would be logistically difficult and costly to deal with the individuals separately. Instead, it could be advisable for the individual purchasers to create a tenant’s association (i.e. an entity where all of the purchasers are members and the land is purchased as a whole). This should allow the land to be sold under one transfer (which is administratively easier), and an association may be more likely to instruct a solicitor where the cost can be shared. If the purchaser appoints a solicitor, this will mean there is more due diligence etc on the sale, but is likely to reduce the overall difficulty, time and expense of the sale.

An alternative would be to sell the allotment land (as permitted) to a local Council or a local Parish Council (a Council). It is fairly common for allotments to be let to tenants by a Council and a Council may be willing to purchase the land, as allotments are considered to be valuable community amenities (and there are certain statutory provisions requiring Councils to provide allotments).

However, it is ultimately decided that land is to be sold, the first step is to identify the basis of each tenants’ occupation and ascertain how such tenancies can be terminated if a sale with vacant possession is to be achieved. As an alternative the land can be sold subject to the tenancies, albeit the range of purchasers for such land could well be limited.