Termination without just cause: FIFA’s new interim rules following Diarra

6th January 2025

“FIFA’s interim amendments to its regulations governing the termination of playing and coaching contracts without just cause look to address some of the concerns the European Court of Justice raised in Diarra. Certain of the changes are likely to be agreeable to most stakeholders. The key battleground will be how compensation is calculated in the event of termination without just cause.”

On 4 October 2024, the European Court of Justice (CJEU) handed down a critical preliminary ruling – the Diarra ruling – on a number of provisions governing the termination of a playing contract without ‘just cause’ in FIFA’s Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (RSTP).

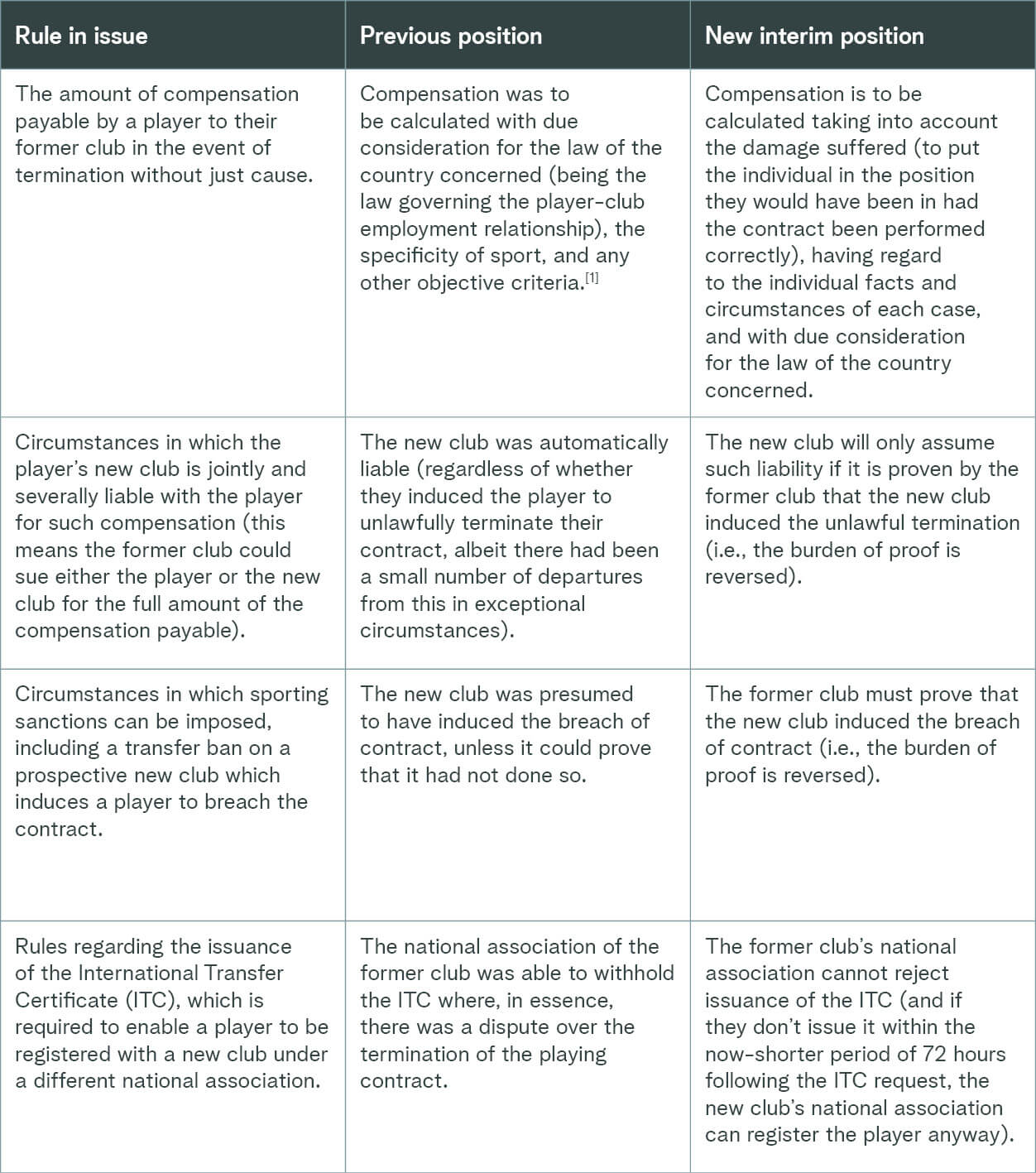

In response, FIFA commenced a global consultation on the challenged rules which is ongoing. In the interim, mindful that January brings with it the first major transfer window following the ruling, FIFA has made some temporary rule changes effective from 1 January 2025.

Diarra and termination without just cause: the background in brief

We broke the Diarra case down in a previous article but, as a very high-level summary, the CJEU considered the relevant provisions of the RSTP to be in breach of certain EU laws, namely, the person’s right to freedom of movement and the prohibition on anti-competitive agreements.

Importantly, it’s permissible to derogate from these EU laws where, broadly speaking, it is necessary to meet legitimate objectives.

The CJEU considered that FIFA has a legitimate objective of ensuring regularity of club competitions, which requires the maintenance of a certain degree of player stability at clubs. The relevant provisions sought to do this by essentially deterring players (and clubs) from terminating their contracts without just cause.

Where FIFA came unstuck was in showing the necessity of their rules to meet that objective (or, in other words, whether the rules were a proportionate means of achieving their objective). FIFA’s interim measures seek to take on board a number of the CJEU’s comments, as well as those of other stakeholders, while acknowledging that more consultation is needed before issuing the final amendments to the regulatory framework.

A summary of the key temporary changes

Definition of just cause

The interim regulatory framework now includes a description of the term ‘just cause’, which seeks to codify the existing position in FIFA and CAS case law: ‘In general, just cause shall exist in any circumstance in which a party can no longer reasonably and in good faith be expected to continue a contractual relationship.’

Comment on the temporary changes to the termination without just cause provisions

The temporary measures are not the finished product, and many more months of consultation is expected.

The reversed burdens of proof in respect of possible liability and sanctions on the player’s new club are in line with the CJEU’s comments and likely to be welcomed by the vast majority of stakeholders. The key battleground is likely to be over the calculation of compensation in the event of termination without just cause.

-

Calculation of compensation

The temporary measures no longer refer to various non-exhaustive factors to be considered in calculating compensation (see footnote [1]) – which were criticised by the CJEU – and instead row back to focusing on the damage suffered by the injured party.

However, case law has recognised the difficulty of quantifying the loss a player causes to their club for termination without just cause. Accordingly, FIFA’s commentary on the RSTP (currently based on the old provisions) summarised the general method adopted by its Dispute Resolution Chamber (DRC) to approximate the loss caused to the club. That method includes various of the now-omitted factors in making that calculation. Given FIFA acknowledges that the DRC’s approach is borne out of the difficulty of quantifying loss, it remains to be seen how the DRC will interpret the amended provisions.

The new provisions also require compensation to be calculated, ‘having regard to the individual facts and circumstances of each case’. While there is no longer an express requirement to give due consideration for ‘the specificity of sport, and any other objective criteria’ (including those listed at footnote [1]), the new wording is still broad enough to capture any criterion the judging body considers relevant.

The CJEU in Diarra was critical of the RSTP referring to general concepts like ‘specificity of sport’ and a lack of precision which made it difficult for anyone to be certain as to how compensation would be calculated (and therefore to verify whether it was properly done). Similar concerns can be levelled at imprecise reference to having regard to the facts and circumstances of the case, although it is anticipated that coming to an agreement on what is included in the RSTP in this regard will be a key sticking point between stakeholders and therefore this is a broad placeholder for now.

Separately, the CJEU in Diarra criticised the fact that the RSTP calculation only required ‘due consideration for’ the law of the country concerned. It noted that FIFA acknowledges such laws are virtually never applied, whereas the CJEU expected ‘actual compliance’ with the law in force in the country governing the player-club relationship. FIFA’s temporary rules don’t address this criticism – ‘due consideration’ is still all that is required and the explanatory note accompanying the temporary measures puts the onus on the party seeking to rely on the laws of the country concerned to prove its relevance, content and effect.

-

Definition of just cause

For completeness, the broad ‘definition’ inserted overlooks the need for just cause to attach to a (sufficiently serious) breach of contract by the other party. On the face of it, it opens the door to premature termination of a contract for reasons unrelated to the conduct of the other party. For example, a club in financial difficulties might argue that it could no longer reasonably and in good faith be expected to continue a contractual relationship with a costly player, to save the long-term future of the club. Similarly, a player who wishes to terminate their contract because they are away from their family and wish to return home permanently for certain personal reasons may take the position that this meets the just cause test.

It is clear from FIFA’s commentary on the RSTP and the existing case law it sought to codify that this was not the intention.

We await the outcome of the full consultation to see how the RSTP will look in its final form.

[1] The RSTP previously listed the following as other objective criteria: remuneration and other benefits due to the player under the existing contract and/or the new contract, the time remaining on the existing contract up to a maximum of five years, the fees and expenses paid or incurred by the former club (amortised over the term of the contract) and whether the contractual breach falls within a certain period of time.